[The excerpts below are from the book Maritime Cybersecurity: A Guide for Leaders and Managers, published in early September.]

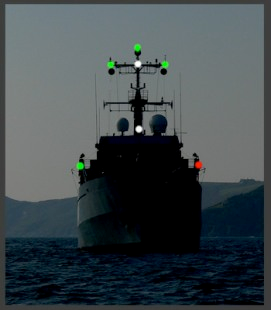

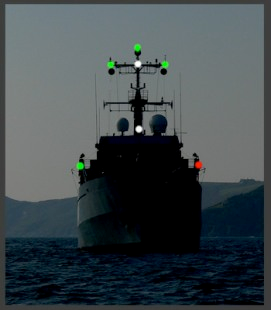

[T]hreats should be put into context. The determine [below] exhibits the sunshine configuration of a vessel that you do not need to see steaming in direction of you at night time. Not solely is that this ship coming in direction of you head-on, it suggests that you’re already in very harmful waters, per Rule 27(f) within the Navigation Guidelines.

Whereas this portrayal has a sure ingredient of darkish humor to it, additionally it is analogous to actual life. When a ship is in a minefield, what’s the actual drawback? Is it the specter of hitting a mine, or is it the vulnerability of the ship to the harm brought on by the explosion? Through the early days of the Battle within the Atlantic throughout World Battle II, Germany deployed magnetic mines in opposition to the British. The mines rose from the seafloor once they detected the small change within the Earth’s magnetic area that occurred when a steel-hulled vessel got here inside vary. The British, upon discovering this mechanism, took countermeasures to successfully degauss their warships. This variation eradicated the mine’s means to take advantage of the ship’s magnetic area and, a minimum of briefly, obviated the risk. The vulnerability of the ship to a mine was not eradicated, however the exploit was defeated.

In our on-line world, we are able to’t management the place the mines are, however we are able to management our susceptibility to getting hit by one and the next harm that would end result.

This results in the next normal fact about cybersecurity:

Vulnerabilities Trump Threats Maxim: If you recognize the vulnerabilities (weaknesses), you’ve bought a shot at understanding the threats (the chance that the weaknesses might be exploited and by whom). Plus, you may even be OK should you get the threats all unsuitable. However should you focus totally on the threats, you’re in all probability in bother.

Threats are a hazard from another person that may trigger hurt or harm. We would or won’t be capable to determine a possible risk, however we can not management them. Vulnerabilities are our personal flaws or weaknesses that may be exploited by a risk actor. Certainly, not all vulnerabilities could be exploited. We’re—or ought to be—in a position to determine our vulnerabilities and appropriate them.

Whereas we can not management the threats, we ought to be educated concerning the risk panorama and have an idea of risk actors who may want to do us hurt, however we must always not obsess over the threats whereas planning a cyberdefense. As a substitute, we must always look inward at our personal techniques, hunt down the vulnerabilities, and plug the holes. New threats at all times emerge, however that doesn’t change the strategic significance of fixing our personal vulnerabilities.

Sarcastically, there’s a corollary to this maxim: “Figuring out threats may help get you funding whereas figuring out vulnerabilities in all probability gained’t.” Virtually all cybersecurity professionals have gone to administration to hunt funds for an emergency replace to {hardware} or software program, simply to be instructed that fixing a susceptible system can at all times wait till the following finances cycle. Conversely, when administration sees a memo from IMO or USCG, or a warning from an ISAC/ISAO, that highlights a reputable risk directed at that very same {hardware} or software program, it’s exceptional how shortly the funds turn into accessible.

——————————————————–

A typical however mistaken perception on the management stage of many organizations, each inside the maritime trade and past, is that the duty for defending info property lies inside the know-how ranks. To those that subscribe to that perception, allow us to share the next: Anybody who thinks that know-how can clear up their issues doesn’t perceive know-how or their issues.

Cybersecurity—or, arguably extra correctly, info safety—isn’t merely, and even primarily, the duty of the IT division. Everybody who is available in contact with info in any form has the duty to guard it and, additional, to acknowledge when it’s beneath assault—and take no matter motion is required to defend it, together with reporting suspected assaults to the suitable defensive businesses inside the group. In the end, it’s the duty of a delegated Chief Data Safety Officer (CISO) to handle the cybersecurity posture of a corporation. That posture contains the creation of a way of urgency and consciousness round cyberthreats at each stage of the group.

It is usually essential to acknowledge that IT and cybersecurity professionals have completely different—albeit usually overlapping—talent units. IT professionals maintain networks working and resilient, and present providers and utility to the customers; cybersecurity professionals defend these property.

——————————————————–

[We wrote this book for] the maritime supervisor, govt, or thought chief who understands their enterprise and the maritime transportation system, however isn’t as aware of points and challenges associated to cybersecurity. Our aim is to assist put together administration to be thought and motion leaders associated to cybersecurity within the maritime area. We assume that the reader is aware of their occupation effectively, information that may assist to supply the perception into how cyber impacts their occupation and group.

Chapter One (The Maritime Transportation System, MTS) offers a broad, high-level overview of the MTS, the assorted parts inside it that we’re attempting to safe, and the dimensions and scope of the problem. Chapter Two (Cybersecurity Fundamentals) provides phrases, ideas, and the vocabulary required to know the articles that one reads and the conferences that one attends that debate cybersecurity.

The subsequent three chapters describe precise cyber incidents in numerous domains of the MTS and their influence on maritime operations. Chapters Three by 5 tackle cyberattacks on delivery strains and different maritime firms, ports, and shipboard networks, respectively. Chapter Six (Navigation Programs) discusses points regarding International Navigation Satellite tv for pc Programs (GNSS) and Computerized Identification System (AIS) spoofing and jamming, whereas Chapter Seven (Industrial Management and Autonomous Programs) presents cyber-related points and the ever-increasing problem of distant management, semi-autonomous, and fully-autonomous techniques discovering their way into the MTS.

Chapter Eight (Methods for Maritime Cyberdefense) discusses practices that tackle cybersecurity operations within the MTS, together with danger mitigation, coaching, the very actual want for a framework of insurance policies and procedures, and the event and implementation of a strong cybersecurity technique. Chapter 9 provides last conclusions and a abstract.

——————————————————–

Creator’s be aware: This guide is meant to talk to all ranges of members of the MTS, from executives, administrators, and ship masters to managers, crew members, and administrative workers. Our hope is that it informs the reader to the next stage of consciousness in order that they are often extra conscious of the threats and be higher ready — at no matter stage of their job — to guard their info property.

As a result of the sphere is so fast-paced, we even have a Web page — www.MaritimeCybersecurityBook.com — the place we are going to submit further info.

Gary C. Kessler is a Professor of Cybersecurity within the Division of Safety Research & Worldwide Affairs at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical College. He’s additionally the president of Gary Kessler Associates, a coaching, research, and consulting firm in Ormond Seashore, Florida.

Steven D. Shepard is the founding father of Shepard Communications Group in Williston, Vermont, co-founder of the Government Crash Course Firm, and founding father of Shepard Photos.

Source: analyticsread