September 9, 2020 MARITIME CYBER SECURITY

Ships are responsible for approximately 3% of all greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions, equivalent to the total emissions of Germany or Japan. Not so much, someone would say. On the table are proposals to slow ships down and slash shipping’s climate footprint, but too many countries and industry bodies are opposed to immediate emergency action.

The Guardian gives more stats:

If shipping were a country, it would be the sixth biggest in terms of emissions share. And it is growing fast – shipping could produce 17% of global emissions by 2050, if left unchecked. About 90% of the world’s trade is carried by sea…

[Shipping] emissions are particularly harmful because they are mostly the result of burning heavy, pollutant-ridden fuels that are usually banned or subject to regulation onshore because of their toxic effects.

Ship fuel produces sulphur, which contributes to acid rain; ships burn more than 3m barrels a day of residual fuel oil, with a sulphur content more than 1,000 times that of petrol for road vehicles.

The dirty fuel also releases black carbon – soot, made up of unburned particles – that is borne on the winds to the Arctic, where it stains the snow and increases the greenhouse effect, because dark snow absorbs more heat.

Since then, the International Maritime Organisation has brought in standards to reduce the use of fuels with sulphur content from 3.5% to 0.5%, enforceable January 2020, and generally aims to reduce its carbon emissions by 50% by 2050. Yet as XR’s Feb 2020 protests pointed out (wearing polar bear suits), what’s still planned to be emitted will still be appallingly destructive (to the Arctic and everywhere else). The IMO’s latest GHG report (August 2020) anticipates a 50% increase in GHGs by 2050 – and reports other horrors, like the methane gas emission from increasingly Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) powered ships.

What COVID (and the economic response to it) will do to international trade is another question… but in any case, shipping seems ripe for a decarbonization revolution, certainly in terms of its propulsion tech.

Cue Smart Green Shipping – an attempt at a commercial consortium, aspiring to innovate towards a zero-carbon emissions status for the sector. The picture above (simulated for them by Immersive Storylab) is their vision of a new class of wind-powered (and when the wind fails, hydrogen-powered) cargo ships.

The story is picked up in detail by a blog from the International Futures Forum in Edinburgh, who hosted Smart Green Shipping’s director Diane Gilpin in conversation last year. She asks the open, fundamental question:

What is shipping for? How is it serving us?

The ship owners are now making money largely from buying and selling ships. They pass costs on to the operators and thus have no incentive to improve efficiency. National governments subsidize shipbuilding to preserve jobs, leading to a glut of low quality, low cost, disposable vessels.

The overcapacity drives down freight rates. Preoccupied with the struggle for survival in the present, there seems to be little appetite to think seriously about the future.

But there are some leverage points in the existing system that might stimulate a different kind of demand and help to feed a new shipping system fit for the 21stcentury.

Drax, for example, needs to import 80m tonnes of biomass into the UK to generate ‘carbon neutral’ electricity. They therefore also have an interest in clean shipping, and the muscle to shape some long term contracts.

Diane has acted as a producer around this opportunity to bring together all the talents and interests required to design and engineer the capacity to retro-fit an existing vessel with cutting edge wind power technology and put a boat in the water by 2021. Drax has agreed to award a long-term contract to the shipowner who does that in a commercially viable way.

The economic case is compelling. Yes, the wind is unpredictable (it does not blow all the time). But what about the cost of oil? Is that predictable – tomorrow, in five years, in thirty? We know what the cost of the wind will be with absolute certainty: zero. The only question is how best to harness that energy.

Retrofitting one ship by 2021 is not enough. Clearly we need to design and build a new fleet of fully renewable vessels. So Diane is now working with an international consortium with the ambition to put a first 100% renewable, commercially viable vessel in the water by 2030 (wind power plus an engine fuelled by hydrogen derived from offshore wind).

…The new ship design will increase initial capital costs but will offer low, predictable long-term operating expenditure. So these ships will be built to last. As Diane says, “they will be loved, looked after, repaired and repurposed as the world changes.” This will demand new financial and business models, which are still being devised. The critical new factor is the predictability in operating costs. As Diane put it, “certainty has a great value in an uncertain world. It remains to be seen how finance will quantify that.”

All of the elements are in now in play: the hardware (the technology and engineering), the software (the data and analytics), and the finance (new business models, insurance, investment). The question is – where to start? Where can we find the right conditions to support this systems innovation, to move from vision to realization?

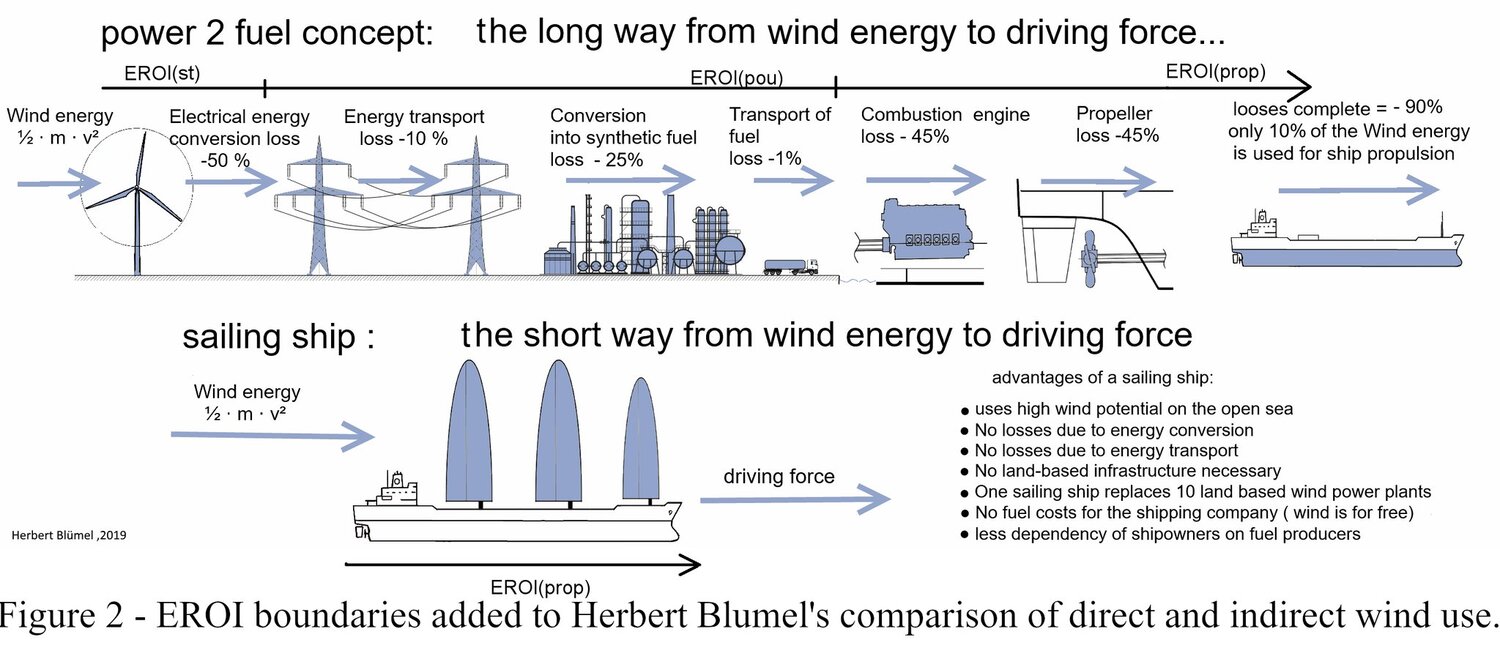

Finally, a graphic that makes the renewable impact of smart Green shipping really clear (click image to enlarge):