COVID-19, ASEAN and the Sino-Vietnam maritime rivalry

May 19, 2020 Maritime Safety News

WHAT’S HAPPENING?

Beijing has established the administrative districts of Xisha and Nansha in the South China Sea, exploiting regional disunity exacerbated by COVID-19 and fortifying its claims in the contested region.

KEY INSIGHTS

– China’s decision to establish the administrative districts will likely serve as a central point of contention in the broader Sino-Vietnamese dispute over the Paracel and Spratly Islands

– China and Vietnam have a long-running dispute over the Islands, which are strategically critical due to their abundant natural resources and role in international trade

– Regional instability brought on by COVID-19, in addition to some Southeast Asian nations’ dependence on Chinese medical supplies, may prevent Vietnam and other claimants from unifying against China in the short-term

BEIJING ASSERTS SOVEREIGNTY

Sino-Vietnamese tensions reached a new high in mid-April when Hanoi protested Beijing’s move to declare two new administrative districts in the contested South China Sea. Beijing’s decision to create the Nansha and Xisha districts, encompassing the Spratly and Paracel Islands respectively, follows an incident on April 4 when Vietnam formally accused a Chinese Coast Guard vessel of ramming and sinking a Vietnamese fishing boat. This represents the most recent point of contention between China and Vietnam, threatening to further destabilise a region plagued by maritime territorial disputes.

Though Sino-Vietnamese tensions in the South China Sea are nothing new, recent events raise significant questions as to how and to what extent Vietnam will shape a unified Southeast Asian response to China when it chairs the upcoming Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in June. Although at the start of this year it appeared inevitable that ASEAN would take a more confrontational stance against China, the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia makes a united ASEAN response uncertain. Despite growing uncertainty regarding ASEAN cohesion during the COVID-19 crisis, the potential for unilateral retaliation by Vietnam remains.

OLD DISPUTES, EVOLVING DIMENSIONS

Photo: @AsiaMTI/Twitter

Sino-Vietnamese tensions in the South China Sea can be traced back to 1974, when Chinese forces seized a portion of the Paracel Islands from South Vietnamese control. Though the sovereignty dispute over the Spratly and Paracel Islands has remained an underlying issue through the early 21st century, tensions between Beijing and Hanoi have noticeably worsened since the late 2000s, when both governments began to more actively exploit South China Sea resources and aggressively police the regions encompassing these resources. Moreover, Chinese President Xi Jinping has pursued a more aggressive, nationalistic strategy regarding these sovereignty disputes, namely by directing land reclamation or “island building” efforts in the Spratlys. In response, Vietnam has indicated its intention to be more assertive in its sovereignty claims in the region. Intensifying rhetoric and increasingly frequent provocation by both sides has resulted in several high-profile diplomatic incidents such as the China-Vietnam oil rig standoff of 2014.

Several economic and geopolitical factors drive competition over the maritime features. The waters encompassed by the two regions host lucrative fishing and hydrocarbon resources. The Vietnamese economy and workforce uniquely rely on access to fishing grounds in the region, where Chinese fishing fleets are also active. Multiple claimants are also exploring the area for energy resources, generation significant friction.

The Spratlys and Paracels play a critical role in international trade. More than $3 trillion in trade cargo passes through the South China Sea each year, including more than 80% of Vietnam’s total trade. Due to the high volume of Vietnamese goods passing through the region, maintaining unrestricted shipping lanes and protecting freedom of navigation is critically important for the Vietnamese economy. As such, it is likely that policymakers in Hanoi fear that ceding control of the Spratlys and Paracels to China would allow Beijing to threaten the Vietnamese economy by restricting this critical trade flow.

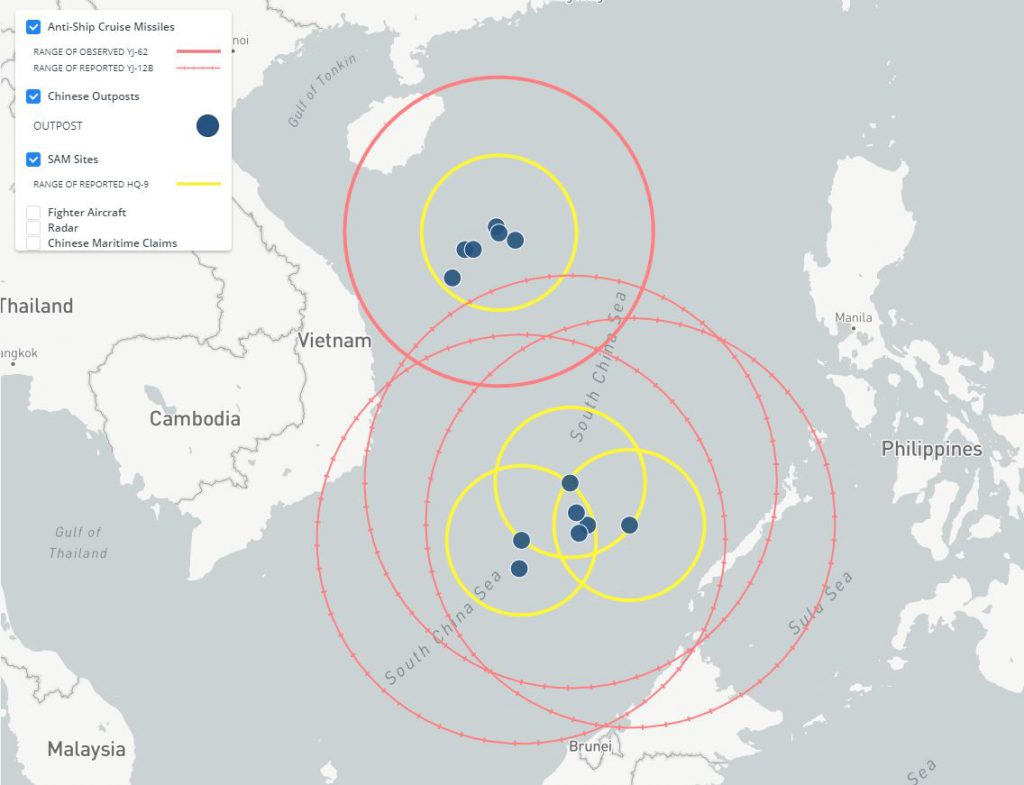

The island regions have also become essential geostrategic and economic assets for China. In its efforts to consolidate administrative control of the majority of the South China Sea, Beijing has constructed radar facilities, harbours, surface-to-air missile silos, and other critical military and dual-use infrastructure on several contested features it administers. These facilities in the Spratlys and the Paracels allow China to apply more directed coercive pressure in Southeast Asia, solidifying its role as a regional security hegemon. Moreover, they enable China to monitor and protect its vital shipping lanes from interference — particularly from the US. Beijing therefore has a strong incentive to expand its administrative control from a select number of islands to the entire set of maritime features encompassed in the Spratly and Paracel regions.

WITH ASEAN NEUTERED, VIETNAM LEFT ON ITS OWN

Photo: Glenn Fawcett/Department of Defense

Southeast Asian states’ dependence on Chinese trade and investment disincentivises any unified pushback against Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea. This phenomenon has been magnified during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many Southeast Asian governments are now dependent on Chinese donations of essential medical supplies. However, unlike other ASEAN states, Vietnam has been remarkably successful at mitigating the spread of COVID-19, largely preventing a domestic crisis and eliminating a need for Chinese assistance. This has created a sharp disconnect between Vietnam and other powerful regional actors. Although Vietnam and the Philippines have expressed outrage at China’s decision to establish the Nansha and Xisha districts, Malaysia and the Philippines have each praised Beijing for providing medical aid. Indonesia has been less vocal in praising Beijing for providing aid, but it remains dependent on Chinese shipments of COVID-19 test kits and personal protective equipment. This disunity between Vietnam and the rest of ASEAN, prompted by China’s “mask diplomacy”, suggests that producing a unified condemnation of Chinese actions in the South China Sea at the upcoming ASEAN Summit in Vietnam will be exceedingly difficult.

Hanoi appears to recognise that any regional appetite for confrontation has vanished, and it appears unlikely that Vietnam will even attempt to force a condemnation of China at the June summit. In a press conference on April 23, a spokesperson for the Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicated that ASEAN, and by extension Vietnam, had committed to “refrain from acts that may complicate the situation and facilitate the efforts of states to combat the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic.” The spokesperson did not explicitly say whether Vietnam considers condemning Chinese action in the South China Sea a potentially complicating act. However, the broad scope of this commitment by ASEAN and the praise other ASEAN members have heaped on China for providing medical aid suggest that Vietnam will refrain from prioritising such a controversial issue at the ASEAN Summit.

Sino-Vietnamese tensions in the South China Sea are not going anywhere, and broader regional disagreements over maritime sovereignty could boil over into destabilising conflict in the future. However, due to both the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis and the importance of Chinese medical aid to ASEAN members, ASEAN as a whole will downplay South China Sea disputes until the pandemic subsides. That said, Vietnam will likely continue to apply unilateral pushback against China for its actions in the South China Sea.