Ship of the Month: Mercy Ships and the Quest to Build Global Mercy

September 24, 2021 Maritime Safety News

Mercy Ships is known globally for its charitable work performing medical procedures in developing countries. For the first time, the organization has a new ship, Global Mercy, recently delivered from a shipyard in China. Jim Paterson, Marine Executive Consultant, Mercy Ships takes Maritime Reporter & Engineering News inside the construction of the world’s largest civilian hospital ship.

Jim Paterson already had a career and Chief Engineer’s Certificate when he joined Mercy Ships nearly 34 years ago, in search of a life change to make a difference. “I sailed commercially for a few years and traveled the world and saw some really sad spots,” said Paterson. “I remember being up the river in Guayaquil in Ecuador and there were people begging for food … they were just so hungry. I got to know my minister back home, and I said, ‘This world just seems a mess. What can I do to make a difference?’”

His minister encouraged him to join an organization where he could leverage his marine engineer skills, which is how he found Mercy Ships. “We had Anastasis, our first ship, and I made an application. I thought we would do two years and go back home again … but here we are 34 years later.”

Paterson and his growing family spent eight years onboard ship, but “as the kids grew and the cabins weren’t getting any bigger,” he came ashore and made home in East Texas by the Mercy Ships headquarters, effectively starting the Mercy Ships Marine Operations Department.

“Prior to that, we did everything from the ship itself: we organized the dry dock, spare parts, everything. It was quite complicated back then, as there wasn’t email; we had to do everything by fax. It was much easier once we established the marine operations department here. With the introduction of the ISM Code, it was actually about to become a requirement.”

With Anastasis approaching the end of its service life, the organization found itself in need of a new ship. After much searching and inspecting various secondhand tonnage, it opted to convert a retired Danish rail ferry ship in the U.K. “The conversion took longer than expected, and we put that ship (Africa Mercy) into service in 2007; but we had already started to dream about another ship,” said Paterson. Living through the pitfalls of a conversion project, the organization started exploring a newbuild, and 2010 the decision was taken by the board to pursue new construction. “We weren’t used to building new ships, our broker friend Gilbert Walter from BRS introduced us to Stena RoRo, who had experience building ships,” said Paterson. So in partnership with Stena RoRo, a Tender Package was prepared and a bid package was sent out by BRS to 12 globally, with Tianjin Shipyard in Tianjin, China, emerging the winner to build the world’s largest civilian hospital ship.

Global Mercy is 174 meters long with a 28.6 meter beam and a 6.4 meter maximum draft, which allows it to go into quite a wide number of ports and not take up too much space. Photo courtesy Mercy ShipsInside Global Mercy

Global Mercy is 174 meters long with a 28.6 meter beam and a 6.4 meter maximum draft, which allows it to go into quite a wide number of ports and not take up too much space. Photo courtesy Mercy ShipsInside Global Mercy

Today Mercy Ships has one operational ship, with the new ship on its way to becoming operational, enroute from China to Europe. “The ship is complete in all respects,” said Paterson, “but the hospital itself still needs to be fitted up and made to work.” Building the ship in China during a global pandemic didn’t help to make the process more efficient, so Paterson said there remains some work to finish the ship’s IT systems. “There’s a lot of work still to do, but once the ship comes online and works with Africa Mercy, we will more than double the impact of Mercy Ships delivering healthcare services to the countries that need it most, and primarily those that happen to be in West Africa.”

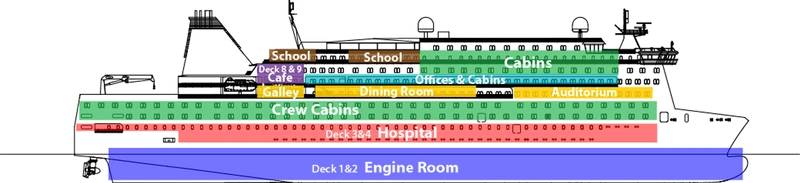

In designing the new ship, the first consideration was size, both to accommodate the needed crew, staff and medical facilities, but also a ship that wasn’t too big, as it is usually on scene for up to 10 months at a time, and many of the African ports are still developing, space constrained and extremely busy.

“So the ship is 174 meters long with a 28.6 meter beam and a 6.4 meter maximum draft, which allows it to go into quite a wide number of ports and not take up too much space,” said Paterson. With 12 decks and a gross tonnage of approximately 38,000, “it’s a big volume and a relatively short length” which allows for a 7,000-square-meter hospital including six operating rooms and 202 beds total, which includes 90 “low care beds for pre- and post-op that don’t need nursing care.”

“The ship is diesel electric (4 x Wärtsilä 6L32s, just under 3MW) because we spend such a long time tied up alongside, we want to maximize the installed power plant, so we rotate the generators through on a regular basis,” said Paterson. Designed by DeltaMarin in Finland, the ship uses ABB pods for propulsion for a 12-knot service speed.

“The amount of fuel that we use to push the ship through the water is quite small. The biggest electrical load actually is the air conditioning, and the air conditioning is probably the most complex part of the ship,” said Paterson. “We used Trident to do the design of the air conditioning and also the commissioning. The HVAC equipment is primarily comprised of four York Centrifugal Chiller Units and Flakt Woods Air Handlers. Airflow in the hospital is quite difficult, and also keeping it as energy efficient as possible with 100% fresh air. That took a lot of effort from Trident commissioning engineers.”

“But otherwise, the ship is pretty much like any passenger ship/RoRo ferry in terms of the construction; nothing too complicated,” said Paterson. “We do have quite a sophisticated waste management system on board, of course. We’ve got an advanced membrane reactor for treating the sewage produced by EVAC. The rest of the dry waste processing plant came from a variety of sources all integrated by the EVAC team. When operating properly the discharge should be fresh water and ash from the incinerator. One of our biggest challenges in the ports we go to is fresh potable water, because we’re sitting there for so long. We have to rely usually on water supply from the shore, sometimes not a problem, sometimes it can be a struggle. So we’re looking at how can we put a water maker on board that will actually make water from harbor water, and that’s easier said than done. We do collect, treat and filter the condensate water from the Air Handlers and use it for technical water such as laundry water.”

In terms of fuel for the ship, ultra low sulfur diesel was the choice, as alternatives such as LNG were not an option premised on the ship’s area of operation and fuel availability. “One of our biggest challenges at the moment is availability of some of these alternative fuels. In West Africa there’s not a lot to choose from, so we’re stuck with diesel for the time being. But the ship can burn different fuels, and in the future (fuel selection) may change.”

Other technical features include sophisticated self-tensioning winches to hold the ship steady for operations, and two large cranes capable of lifting 31 tons for lifting supplies on and off. “We send a couple of containers every month to keep the hospital going, and of course supply food, too.”

Aside from the challenges presented by COVID, Paterson said the newbuild process proceeded relatively smoothly, particularly given that this was the largest civilian hospital ship of international class ever built. “We were blessed to have a senior surveyor from Lloyd’s Register who had quite a bit of welding experience, and he actually taught the shipyard how to weld thin plate without buckling it,” said Paterson. “So the shipyard was grateful for that, and after the first couple of blocks, I’ve heard people comment, ‘You couldn’t get blocks better than this in Europe.’”

One hurdle to overcome early was the ‘Safe Return to Port’ mandate, “which actually set us back quite a bit on the design period. The safe return to port says you have to have an advised speed of 6 knots in Beaufort force eight if you lose half your propulsion. Well, if you only have 12 knots to start with and you’re trying to do six knots at Beaufort force eight, that’s quite a challenge.

Working with the designers, the shipyard, the flag state (Malta) and LR, the ABB pods ended up as the game changer as steering the ship at slower speeds in rough conditions was achievable. “You can steer a ship, basically, just over zero knots with podded propulsion,” said Paterson. “So once the shipyard got comfortable with that, we moved ahead. During the tank tests, she was doing six knots on one pod no problem. At sea trials, although the design speed is 12 knots, we actually were sailing along at 16 knots at one point. So she far outperformed her design.”

The Volunteer Model: The Global Mercy will be operated by a full crew complement of *650+ skilled crew of mariners, medical professionals, galley staff, teachers, and many other professions with two things in common – they love the mission of Mercy Ships and they’re volunteering their time. In fact, it is this volunteer model that has allowed for Mercy Ships to deliver free healthcare services for more than 40 years. With the addition of the Global Mercy to the Mercy Ships fleet of hospital ships, the need for volunteers to join the Mercy Ships family will continue to grow. Explore and learn more by visiting https://opportunities.mercyships.org/

Photo courtesy Mercy Ships

Photo courtesy Mercy Ships

Global Mercy Equipment List

Ship Name: Global Mercy

Ship Type: Hospital Ship

Ship Builder: Tianjin Xingang Shipyard

Material: Steel

Ship Owner: Mercy Ships

Ship Operator: Mercy Ships

Ship Designer: Deltamarin

Delivery Date: June 16, 2021

Classification: Passenger Ship

Main Particulars

Main Particulars

Length, (o.a.): 174 m

Length, (b.p.): 167 m

Breadth, (molded): 28.6 m

Depth, (molded): 9.5 m

Draft, (designed): 6.1 m

Draft, (scantling):6.4 m

DWT (at design draft): 6,523

Speed: 12 knots service, 14 knots top speed

Fuel Type: HFO // MGO

Main engines: 2 x ABB Azipod CO1400L 4 blades 3.8m diameter propulsion units

Total installed power: 4 x2, 880kW

Bow Thrusters: 1 x Berg 1500kW

Propellers: 2 x ABB Azipod CO1400L 4 blades 3.8m diameter propulsion units

Diesel Generators: 4 x Wartsila 6L32 2,880kW each driving ABB Alternators 690V 60Hz

Engine controls: Kongsberg

Radars: Furuno x2 FAR2127; x1 FAR3000

Depth Sounders: Furuno FE-800

Auto Pilot: Keiki PR-9000-E

Radios: Furuno SSB FS 2575C; x2 Furuno VHF FM-8900S

AIS: Furuno x2 FA-170

GPS: Furuno x3 GP170

GMDSS: Furuno x2 Felcom 18, 1 Felcom 19,

SatCom: Furuno FB-8000

Mooring equipment: MacGregor x5 mooring winches 200EW, MacGregor x2 anchor windlass/mooring winch

Fire extinguishing systems: SEMCO. Watermist system.

Fire detection system: Consilium

Heat exchangers: Alfa Laval, Heatmaster

Motor starters: Vacon, ABB Variable Frequency Drives

Lifeboats: Palfinger x2 130 Person plus Palfinger 2 x 70 person combined Lifeboat Rescue Boat

Liferafts: Viking x 10 25 Person inflatables

Coatings: Jotun

Ballast Water Management System: Headway

Deck Cranes KGW x2 with two hooks 31T and 5T

Stores and Passenger elevators (6) Kone

Hospital equipment Phillips Cat Scan, Steris washer disinfectors/sterilizers, etc.

SOURCE READ THE FULL ARTICLE

https://www.marinelink.com/news/ship-month-mercy-ships-quest-build-global-490740