The International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) has published nine of its 12 recommendations on cyber safety for ships.

IACS initially addressed the subject of software quality with the publication of UR E22 in 2006. Recognizing the huge increase in the use of onboard cyber-systems since that time, IACS has developed this new series of recommendations with a view to reflecting the resilience requirements of a ship with many more interdependencies. They address the need for:

• A more complete understanding of the interplay between ship’s systems

• Protection from events beyond software errors

• In the event that protection failed, the need for an appropriate response and ultimately recovery.

• In order that the appropriate response could be put in place, a means of detection is required.

Noting the challenge of bringing traditional technical assurance processes to bear against new and unfamiliar technologies, IACS has launched the recommendations in the expectation that they will rapidly evolve as a result of the experience gained from their practical implementation. So, as an interim solution, they will be subject to amalgamation and consolidation.

More than 90 percent of the world’s cargo carrying tonnage is covered by the classification design, construction and through-life compliance rules and standards set by the 12 member societies of IACS.

The 12 Recommendations are:

Recommended procedures for software maintenance of shipboard equipment and systems (published)

Shipboard equipment and associated integrated systems to which these procedures apply can include:

– Bridge systems;

– Cargo handling and management systems;

– Propulsion and machinery management and power control systems;

– Access control systems;

– Ballast water control system;

– Communication systems; and

– Safety system.

Recommendation concerning manual / local control capabilities for software dependent machinery systems (published)

IMO requires through SOLAS that local control of essential machinery shall be available in case of failure in the remote (and for unattended machinery spaces, also automatic) control systems. For traditional mechanical propulsion machinery, this design principle is well established. The same design requirement applies to computerized propulsion machinery, i.e. complex computer based systems with unclear boundaries and with functions maintained in the different components.

Contingency plan for onboard computer based systems (published)

Computer based systems are vulnerable to a variety of failures such as software malfunction, hardware failure and other cyber incidents. It is not possible for all failure risks to be eliminated so residual risks always remain. In addition, a limited understanding of the operation of complex computer based systems together with fewer opportunities for manual operation can lead to crews being ill-prepared to use their initiative to responding effectively during a failure.

IMO and Classification Society rules contain many context specific examples of requirements for independent or local control in order to provide the crew with the means to operate the vessel in emergencies or following equipment failures. These requirements have generally been introduced when automation or remote control is introduced to individual pieces of equipment or functions and address concerns regarding its possible failure of the new features. The introduction of technologies which integrate different vessel’s functions creates the opportunity for two or more systems to be impacted by a single failure simultaneously.

Where, due to high computer dependence, manual operation is no longer practical or where the number of systems simultaneously affected is too high for manual operation to be practical with existing crew levels then the value of local control as a form of reassurance is limited, however the crew will still need to be provided with practical options to try to manage threats to human safety, safety of the vessel and/or threat to the environment.

If the practical options are not considered during the design and installed during construction of the vessel then the vessel and its crew could be, due to the introduction of new technologies, exposed to risks which they cannot manage.

Practical options could include limiting the extent of potential damage so that manual control is still achievable or providing backup systems which could be used in a worst case systems failure. Whatever form of contingency is provided to address failures it is important that it is well documented, tested and that the crew is aware and trained.

Requirements related to preventive means, independent mitigation means, engineered backups, redundancy, reinstatement etc. are dealt with in the other relevant recommendations.

Network Architecture (published)

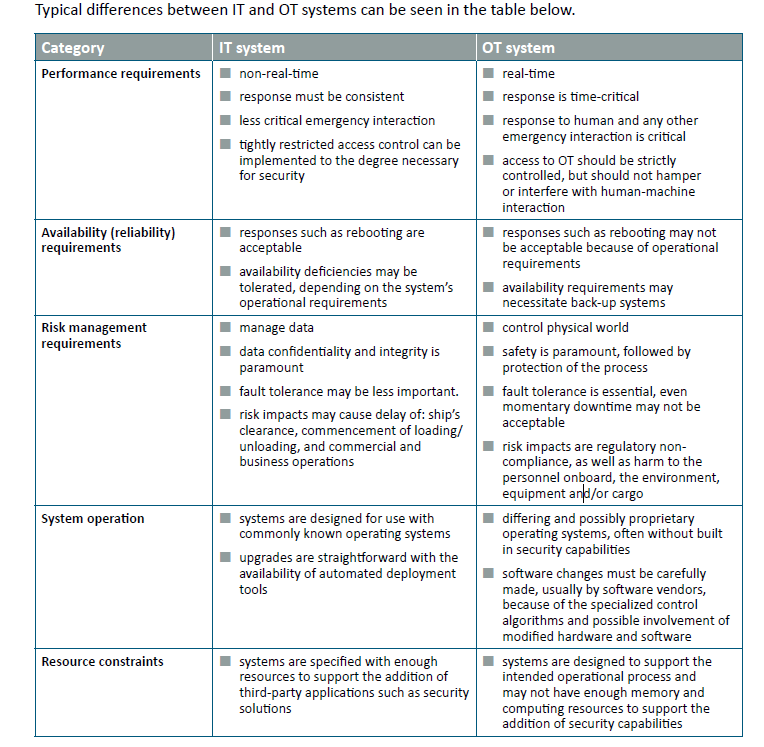

Ship control networks have evolved from simple stand-alone systems to integrated systems over the years and the demand for ship to shore remote connectivity for maintenance, remote monitoring is increasing.

Incorporation of Ethernet technology has resulted in a growing similarity between the once disconnected fieldbus and Internet technologies. This has given rise to new terms such as industrial control networking, which encompasses not only the functions and requirements of conventional fieldbus, but also the additional functions and requirements that Ethernet-based systems present.

The objective of the present recommendation is to develop broad guidelines on ship board network architecture. The recommendation broadly covers various aspects from design to installation phases which should be addressed by the Supplier, system integrator and yard.

Data Assurance (published)

Regulation strongly focuses on system hardware and software development, however, data related aspects are poorly covered comparatively. Data available on ships has become very complex and in a large volume, meaning a user is unlikely to spot an error and it would be unreasonable to expect them to do so. Cyber systems depend not only on hardware and software, but also on the data they generate, process, store and transmit. These systems are also becoming more data intensive and data centric, often used as decision support and advisory systems and for remote digital communication.

Data Assurance may be intended as the activity, or set of activities, aimed at enforcing the security of data generated, processed, transferred and stored in the operation of computer based systems on board ships. Security of data includes confidentiality, integrity and availability; the scope of application of Data Assurance covers data whose lifecycle is entirely within on board computer based system, as well as data exchanged with shore systems connected to the on board networks.

Physical Security of onboard computer based systems (to be published Q4, 2018)

Network Security of onboard computer based systems (published)

Network security of onboard computer-based systems consists in taking physical, organizational, procedural and technical measures to make the network infrastructure connecting Information Technology and/or Operational Technology systems resilient to unauthorized access, misuse, malfunction, modification, destruction or improper disclosure, thereby ensuring that such systems perform their intended functions within a secure environment.

Vessel System Design (to be published Q4, 2018)

Inventory List of computer based systems (published)

For effective assessment and control of the cyber systems on board, an inventory of all of the vessel’s equipment and computer based systems should be created during the vessel’s design and construction and updated during the life of the ship: tracking the software and hardware modifications inside ship computer based systems enables to check that new vulnerabilities and dependencies have not occurred or have been treated appropriately to mitigate the risk related to their possible exploitation.

Integration (published)

Integration refers to an organized combination of computer-based systems, which are interconnected in order to allow communication and cooperation between computer subsystems e.g. monitoring, control, Vessel management, etc.

Integration of otherwise independent systems increases the possibility that the systems responsible for safety functions can be subject to cyber events including external cyberattacks and failures caused by unintentionally introduced malware. Systems which are not directly responsible for safety, if not properly separated from essential systems or not properly secured and monitored in an integrated system, can introduce routes for intrusion or cause unintended damage of important systems. It is necessary to have a record and an understanding of the extent of integration of vessels’ systems and for them to be arranged with sufficient redundancy and segregation as part of an overall strategy aimed at preventing the complete loss of ship’s essential functions.

Remote Update / Access (published)

Information and communications technology (ICT) is revolutionizing shipping, bringing with it a new era – the ‘cyber-enabled’ ship. Many ICT systems on-board ships connect to remote services and systems on shore for monitoring of systems, diagnosis and remote maintenance, creating an extra level of complexity and risk. ICT systems have the potential to enhance safety, reliability and business performance, but there are numerous risks that need to be identified, understood and mitigated to make sure that technologies are safely integrated into ship design and operations.

Communication and Interfaces (to be published Q4, 2018)