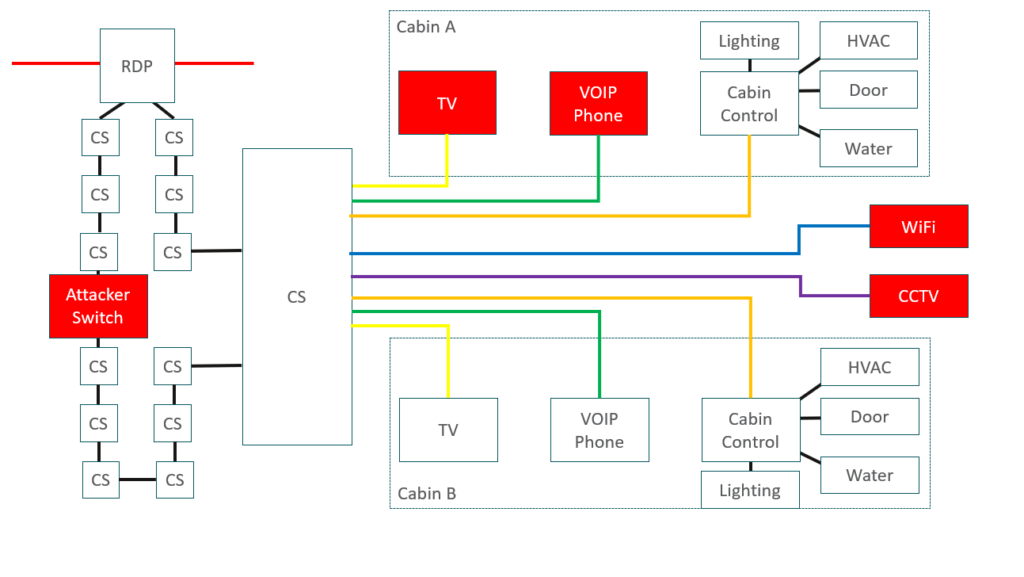

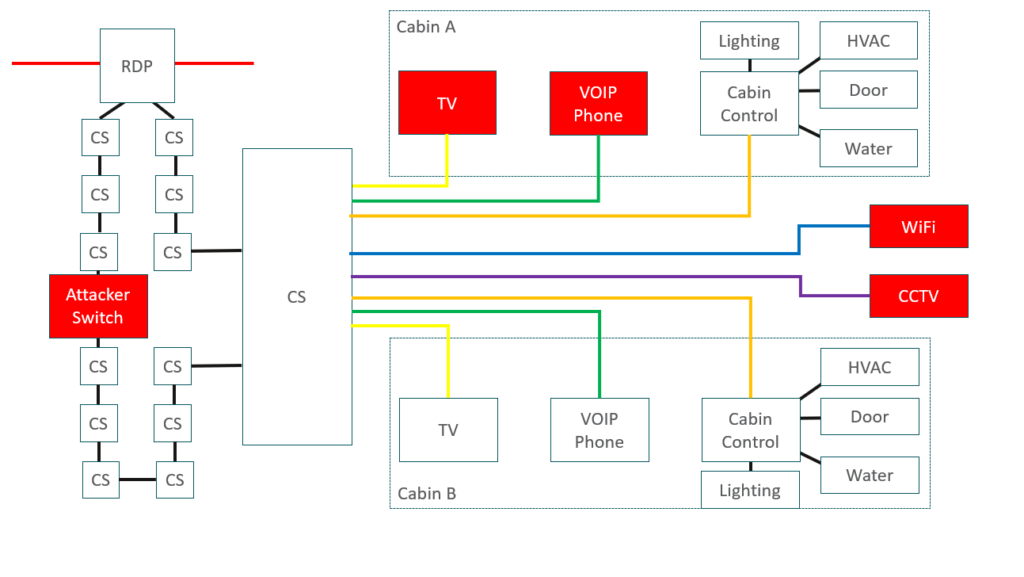

As mentioned the cabin switch appeared to be the key to all our access requirements. From that we could get to the trunk network, and all those TV, VOIP, and Wi-Fi services, a raft of different VLANs that are very interesting to an attacker.

Physically the big problem was that cabin switch was located in the narrow passageway corridor between cabins. In that small space I had to open a panel, open the box it was in then physically unscrew the switch and then connect to it to mess about with it. It meant being in the way of foot traffic.

As only a few of the ship’s crew knew what we were onboard for we really needed to stay incognito. That’s quite a challenge on a vessel with 500 CCTV cameras and plenty of people walking about, we’re getting in their way and getting noticed. The solution to staying under the radar was to do it all from inside our cabin, which was no mean feat.

First we unplugged the ethernet cables from the back of our TV and VOIP phone. We then went to the cabinet in the wall in the passageway, where we bridged directly onto the trunk with those cables. This meant that we had taken our cabin switch out of the network so it was feeding into our cabin via this structured cabling that was already installed. That solved part of the problem.

We then put our own switch into that loop so now we were part of that VLAN trunk, nicely connected to that big loop. It meant we could intercept all of the traffic on the VLANs and we could connect to all of the devices on those VLANs too. While we managed to get the TVs default passwords we couldn’t really do much apart from stopping them working. The VOIP phones also had default passwords, but again we were limited to changing their settings so they didn’t work. The Wi-Fi was quite secure so there wasn’t much we could do to that either.

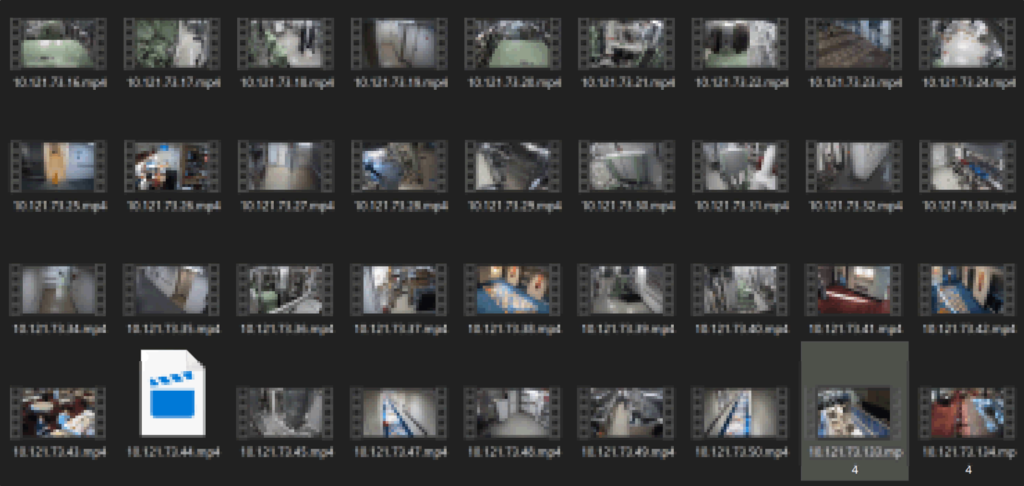

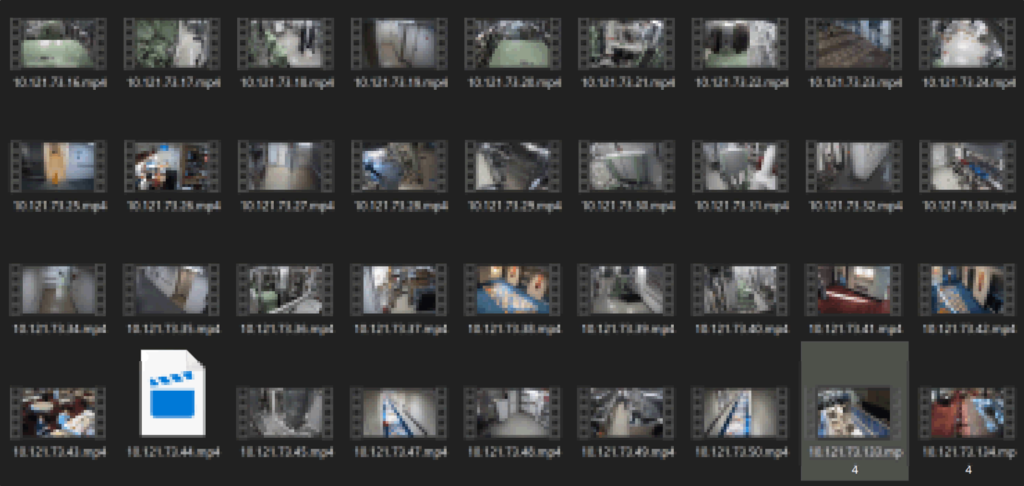

The CCTV was different though. The CCTV and Video Management System (VMS) connected out to all of the cameras using RTSP, a plain text protocol. The cameras required a properly authenticated login, but we could intercept this and so connect to the cameras- all of the cameras on the ship. Now we could watch all the video feeds from the comfort of our cabin.

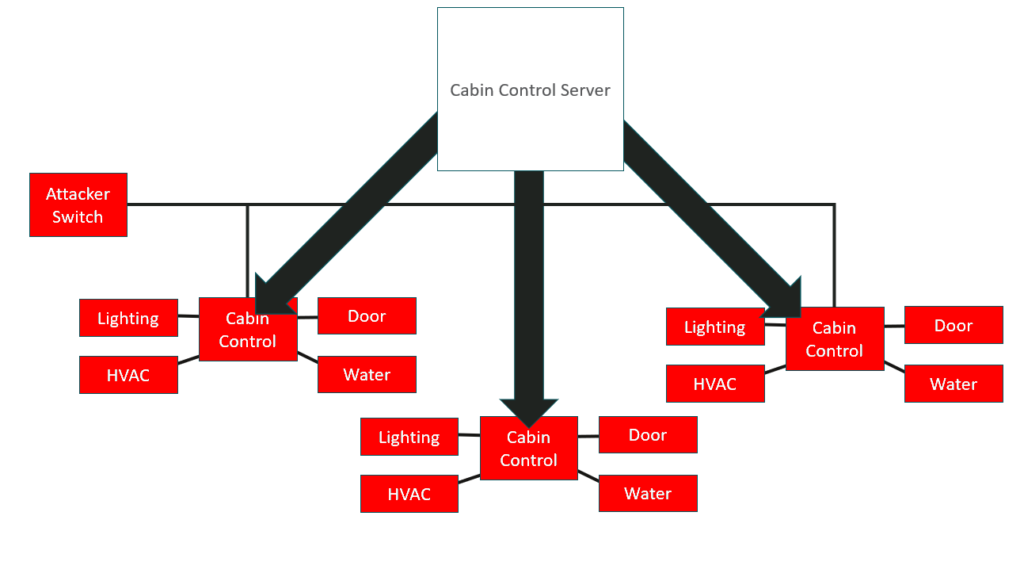

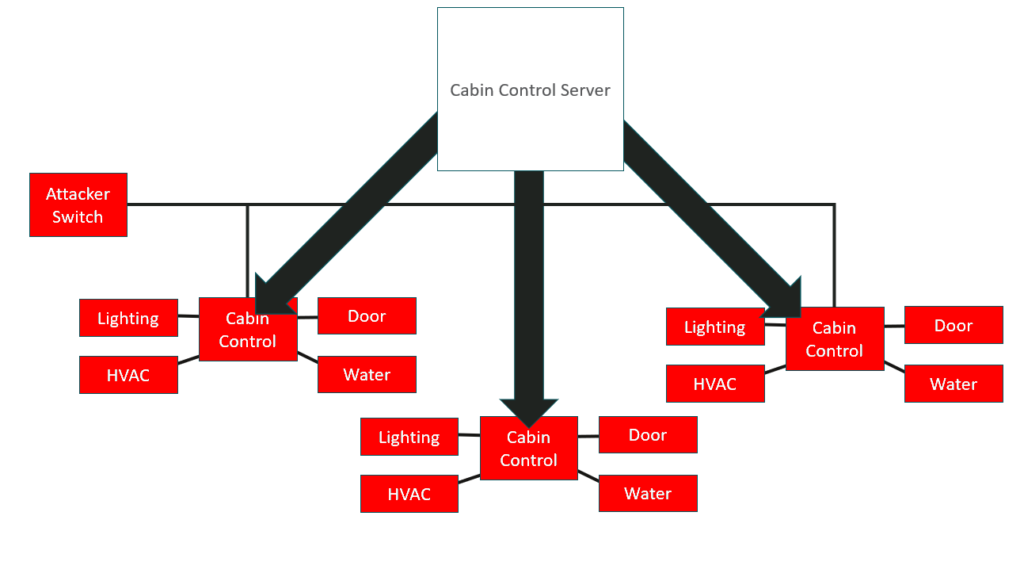

After that we reviewed the cabin control system for the lighting, HVAC, door, and water. Most systems like this with hundreds of nodes will connect back to a service. They usually make a connection from the device through to the server, but this one was a different as it worked the other way around.

Here the cabin control server established connections out to the controls in the cabins. While this was unusual it meant we didn’t have to compromise the cabin control server to interact with the cabin controls. We were on the VLAN that they were all on so we could come along with our switch and directly compromise all of the cabin controls. We could turn the lights on and off, we could mess about with the aircon, we could lock people out of their cabins, and we could even open doors on the accessibility cabins- the ones with automated doors.

With all of these areas covered we could negatively affect the passengers, to make them uncomfortable or even cause some distress. This means that they will complain, en masse, and that is going to be very expensive to manage.

The other thing we thought would be amusing would be writing something on the side of the ship using cabin lighting, by turning certain cabin’s lights on or off to create a pattern or word viewable from a distance outside. Some ships have this functionality where through the cabin control system uses them as a sort of grid through which you can write things on the side of the vessel.

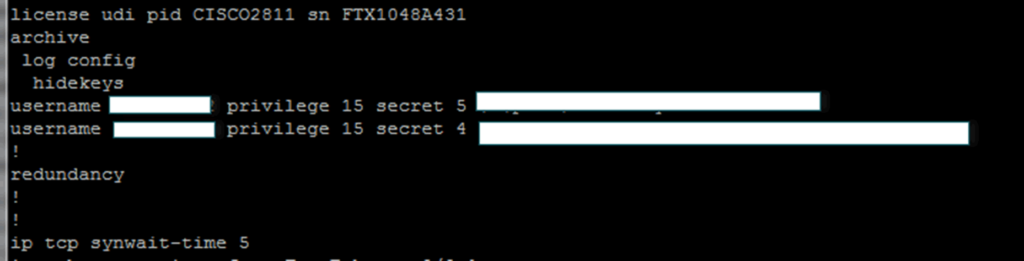

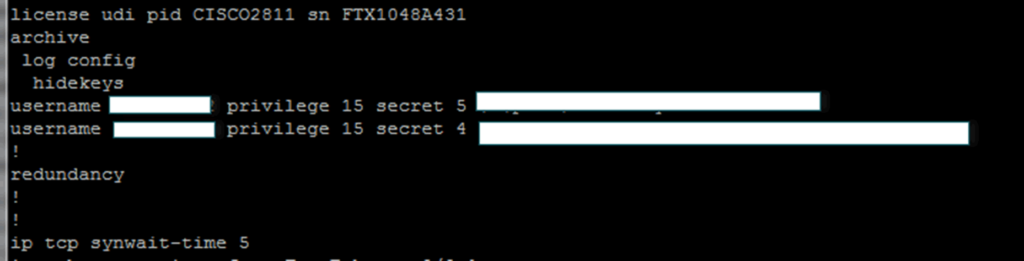

The serious issue here is that the switches were physically accessible to us. Of course we had to be in the passageway for physical access but there’s a common attack that we regularly carry out against switches. Most Cisco switches have a password recovery mode. It means that you can reboot the switch, and through its serial console dump the config file.

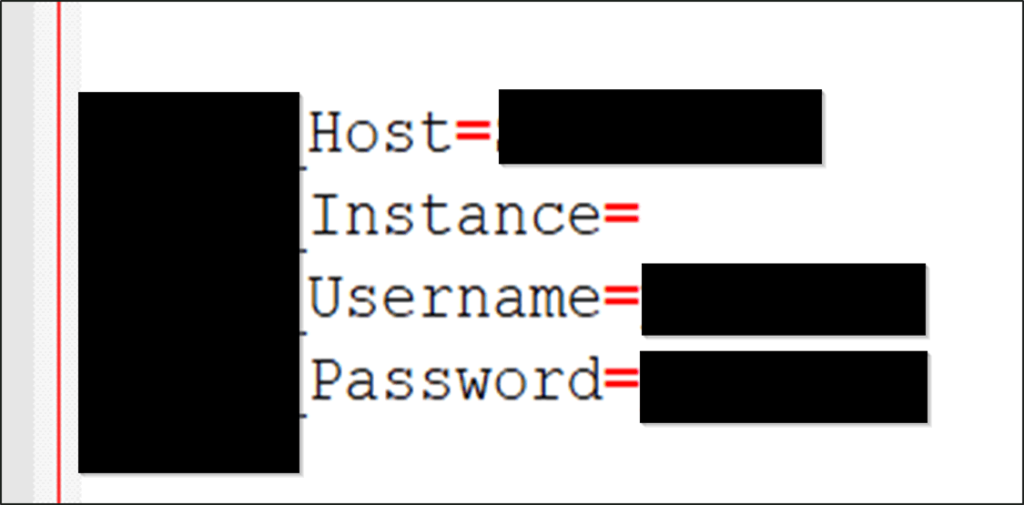

That config file contains information on existing VLANs, such as hashes or possibly even encrypted versions of the passwords. After dumping a config off one of the cabin control switches (taking two or three minutes) we had the hashed passwords. Once transferred to our cracking rig it took about two days to recover them:

The password here was reasonably good, it wasn’t “cisco” or “ship” for example.

We tried it against the cabin switches but none of them had a network logon. However we could plug in via serial and connect that way but that’s not particularly bad. However, as we’ve got access to this trunk we’ve also got access to those RDPs. We found that one of the RDPs had its management interface left exposed to the trunks that we could access, and that RDP had left the web interface enabled, which is bad.

That username and password we recovered from one cabin switch worked on that single RDP. It appeared that during commissioning that particular single RDP hadn’t fully been commissioned- they hadn’t changed the password. We gained access to that RDP and that allowed us to intercept all of the traffic on that fibre trunk. We weren’t just able to access the things on the cabin switch loops anymore, we could see pretty much everything on the vessel, excluding the ICMS industrial control systems.

These VLAN trunks run all over the ship. You can connect from inside the cabin using the TV and phone cables, get access to many systems as well as sniff to get any plain text auth. So, not using https actually had a serious impact here. One brute forcible password that worked on just one part of the core network allowed us to intercept all of the VLAN trunks. That is a significant compromise.

Now this was just an omission, and it did take quite a lot of effort to get to this point but it was a problem of vulnerability.

Issue 4: I Am The Captain Now!

If you’ve been on a cruise recently you’ll have seen crew carrying tablet devices. When there’s a muster or safety drill they’ll be taking muster on a tablet. If you order in one of the restaurants it will be on a tablet. If they come to your room with room service they will have a tablet.

This is usually called a Passenger Management System (PMS) and it deals with cabin assignment and access control. As a result it’s linked to access control system, to allow the management of cabin key cards. It also does booking and billing in the restaurant, it does mustering, and it also can hold your passport details for Immigration. It’s core to how the vessel operates.

All the tablets on this vessel used 8021x certificates for the Wi-Fi, and the tablets were actually quite well hardened. We couldn’t get anything off them easily so we couldn’t get those certificates to gain access to the Wi-Fi. We could have spent time doing something to possibly root one of the tablets or gain the credits from somewhere else.

But why go to those lengths when we’ve already got access to every VLAN on the vessel including the VLAN that carries the Wi-Fi traffic from all of the tablets? We can intercept that traffic, which is what we did.

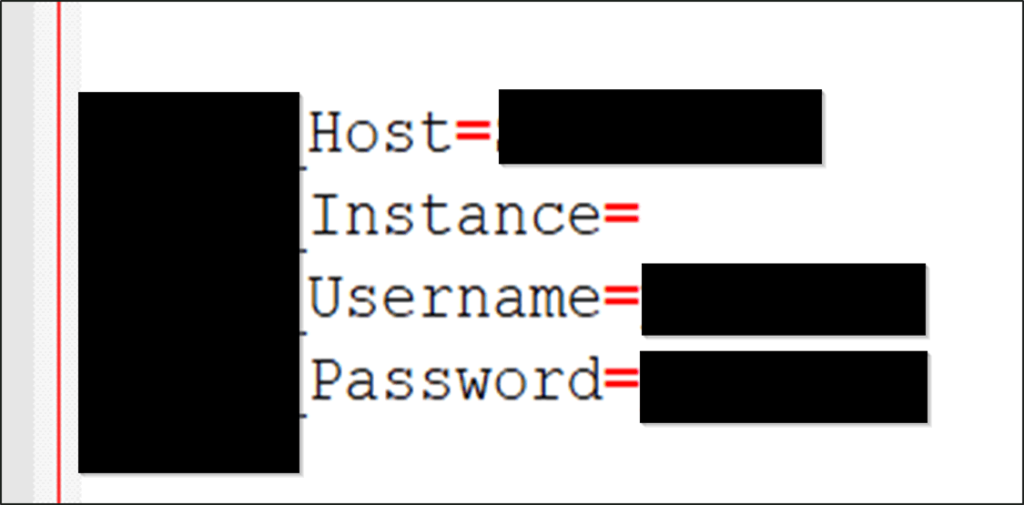

The tablet’s 8021x was implemented by the cruise company as they wanted to layer that layer of security. However the PMS used http so there was no encryption between the tablets and the server. That let us sniff credentials amongst other the network traffic. What we found was an SQL server which was passing its username and password in the plain, across this network. Once we gained access to those VLAN trunks we could get this username and password:

We could then add our own user into the PMS and we could pretty much do what we want. For example, I could book myself into the best restaurant on the ship and not have to pay for it.

The best bit was being able to log in as the captain! We could go to the restaurant, order the most expensive bottle of wine and bill it to the captain. This is a serious impact. The PMS had good Wi-Fi security that was put in place by the cruise company but the PMS vendor used http for the communications, and that just wasn’t secure enough.

We’ve covered those common SQL creds but we’ve not managed to test them on any other ships. It’s possible they could be the same across other ships, meaning we could arrive on board and pretend to be anyone from the crew.. We could wipe details, we could order things in restaurants. I think we comprehensively owned this ship.

Conclusion

- The attacks required detailed knowledge

- It was third-parties who introduced most risks

- Denial-of-Service is very costly

- Cruise ships are fun

These attacks did require detailed knowledge. We had to be on the vessel and we had to have a good level of understanding. One of the problems with a ship is that it’s hard to perform things like intrusion detection remotely. You might be able to sniff traffic but you’ve only got limited amount of bandwidth to send that back to a SoC. On this engagement no-one really noticed us, we dressed smartly and the couple of times that people noticed us opening cabinets and things like that no one said anything. That isn’t always going to be guaranteed though.

Most of the issues we found were introduced by third parties. The cruise company had done a lot to secure those networks but it was third parties putting systems in and making mistakes, and just not doing security properly, that created the problems.

For a ship a Denial of Service is extremely costly. If you can stop a cruise ship leaving its berth (especially in one of the smaller ports where there are only one or two berths) and another ship is waiting to dock, the port can charge huge sums of money. We’re talking tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars per day.

The fallout is that you’ll have passengers complaining, you’re going to possibly have to reschedule flights, maybe get hotels for people, your next cruise may be delayed.

Crashing cruise ships into each other is the stuff of movies, and that’s fine for Hollywood. The real impacts however come from hackers being able to cause your passengers annoyance, discomfort, and distress.

Source: pentestpartners

With our cyber security partner we are providing a weekly list of Motor Vessels where it is observed that the vessel is being impersonated, with associated malicious emails.

With our cyber security partner we are providing a weekly list of Motor Vessels where it is observed that the vessel is being impersonated, with associated malicious emails.