Also available in Japanese.

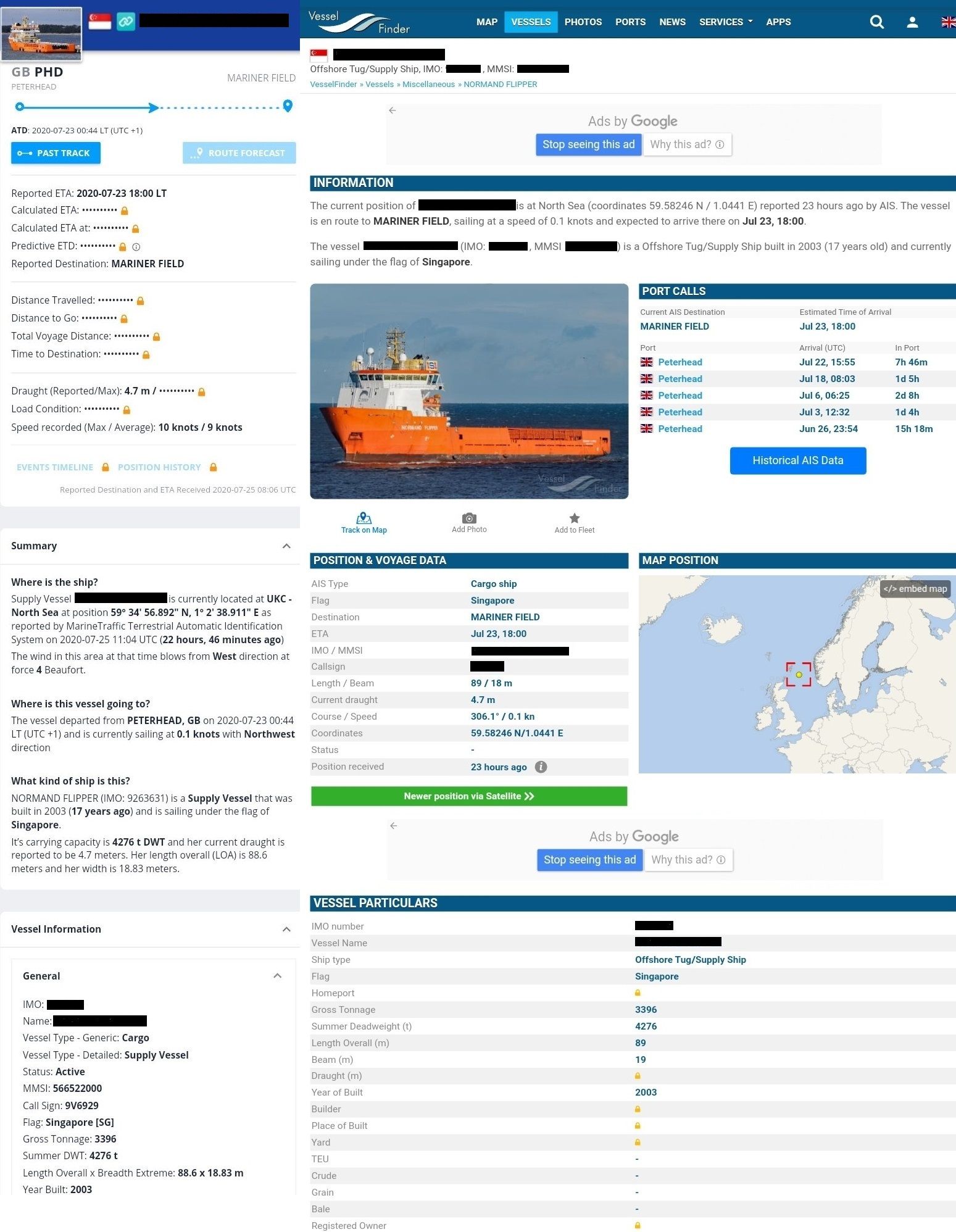

To cope with operational issues such as denied physical access, quarantined vessels and travel restrictions, shipowners are now actively opening for remote access and implementing remote digital survey tools towards vessels and encouraging shore staff to work remotely from home.

There is also increased use of mobile devices to access operational systems onboard vessels and core business systems in the company. Unprotected devices could lead to the loss of data, privacy breaches, and systems being held at ransom. Data is an asset and protecting it requires a good balance between confidentiality, integrity and availability.

In an era of cyber everywhere, with more technological transformation, use of cloud, and broader networking capabilities towards vessels, the threat landscape continues to increase. Cyber-criminals will look to attack operational systems and backup capabilities simultaneously in highly sophisticated ways leading to destructive cyber attacks. Cyber security depends not only on how company and shipboard systems and processes are designed but also on how they are used – the human factor.

Cyber risks may not be easy to identify

Criminals trying to exploit the maritime industry, the vessels and their crew are well organised and continuously evolve in the way they operate. This reflects the constantly evolving nature of cyber risk in general. Approaches to cyber risk management need to be company- and vessel specific but must also be guided by requirements contained in relevant national, international and flag state regulations.

Shipowners and operators who have not already done so, should undertake risk assessments and incorporate measures to deal with cyber risks in their ship’s safety management systems (SMS) and crew awareness training. Shipowners and operators should also embed a culture of cyber risk awareness into all levels and departments in the office and on board the vessels. The result should be a flexible cyber risk management regime that is in continuous operation and constantly evaluated through effective feedback mechanisms.

Most Classification societies (Class) and several marine consulting companies have issued guidelines and recommendations on cyber security onboard vessels. Class, as a Recognized Organization on behalf of Flag State authorities, may now also deliver ISM audits which include cyber risk.

Class is also offering a voluntary cyber secure class notation for verifying secure vessel design and operation and cyber secure type approval to support manufacturers with cyber-secure systems and components. As an advisor, Class may also offer cyber security risk assessment, improvement, penetration testing and training support both on board and in the office.

At Gard we strive to protect the interests of our Members and clients in the best possible way. Our recommendation is to take a holistic approach to the cyber risks to protect the confidentiality, integrity and accessibility of both IT and OT systems through measures covering processes, technology and most importantly people. The easiest and most common way for cyber criminals to gain access, is through negligent or poorly trained individuals.

Recommendation No.1: Focus on policies, procedures and risk assessments

The latest Guidelines on Cyber Security Onboard Ships anticipates that cyber incidents will result in physical effects and potential safety and/or pollution incidents. Therefore, companies need to assess the risks arising not only from the use of IT equipment but also from OT equipment onboard ships and establish appropriate safeguards against cyber incidents involving either of these.

Company plans and procedures for cyber risk management must be aligned with existing security and safety risk management requirements contained in the ISPS and ISM Codes as included in company policies. Requirements related to training, operations and maintenance of critical cyber systems should also be included in relevant documentation on-board.

The IMO Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) adopted Resolution MSC.428(98) on Maritime Cyber Risk Management in Safety Management Systems in June 2017. The resolution states that an approved safety management system should include cyber risk management in accordance with the objectives and requirements of the ISM Code, no later than the first annual verification of a company’s Document of Compliance after 1 January 2021.

Based on the recommendations in MSC-FAL.1/Circ.3, Guidelines on maritime cyber risk management, the resolution confirms that existing risk management practices should be used to address the operational risks arising from the increased dependence on cyber enabled systems. The guidelines set out the following actions that can be taken to support effective cyber risk management:

- Identify: Define the roles responsible for cyber risk management and identify the systems, assets, data and capabilities that, if disrupted, pose a risk to ship operations.

- Protect: Implement risk control processes and measures, together with contingency planning to protect against a cyber incident and to ensure continuity of shipping operations.

- Detect: Develop and implement processes and defenses necessary to detect a cyber incident in a timely manner.

- Respond: Develop and implement activities and plans to provide resilience and to restore the systems necessary for shipping operations or services which have been halted due to a cyber incident.

- Recover: Identify how to back-up and restore the cyber systems necessary for shipping operations which have been affected by a cyber incident.

The Document of Compliance holder is ultimately responsible for ensuring the management of cyber risks on board. Where the ship is under third party management, the ship manager is advised to reach an agreement with the shipowner as to who is responsible for this matter. Emphasis should be placed by both parties on the split of responsibilities, alignment of pragmatic expectations, agreement on specific instructions to the manager and possible participation in purchasing decisions as well as budgetary requirements.

Apart from the ISM requirements, such an agreement should take into consideration additional applicable legislation such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or specific cyber regulations in other coastal states. Managers and owners should consider using these guidelines as a base for an open discussion on how best to implement an efficient cyber risk management regime onboard. Any agreements on responsibility for cyber risk management should be formal and in writing.

Companies should also evaluate and cover service providers’ physical security and cyber risk management processes in supplier agreements and contracts. Similarly, coordination of the ship’s port calls is a highly complex task being both global and local in nature. It includes updates from agents, coordinating information with all port vendors, port state control, handling ship and crew requirements, and electronic communication between the ship, port and authorities ashore.

Agents’ quality standards are important because like all other businesses, agents are also targeted by cyber criminals. Cyber enabled crime, such as electronic wire fraud and false ship appointments, and cyber threats such as ransomware and hacking, call for mutual cyber strategies and cyber enhanced relationships between owners and agents to mitigate these risks.

Recommendation No.2: Ensure that system design and configuration are safe and fully understood and followed

The problem with procedures is that good intentions can become paper pushing exercises. It is therefore important to ensure that those performing tasks involving cyber security understand that the purpose of the procedures is to prevent unauthorised access and not simply to satisfy the regulators or their immediate superiors.

Unlike other areas of safety and security, where historic evidence is available, cyber risk management is made more challenging due to the lack of facts about incidents and their impact. Until we have such evidence, the scale and frequency of attacks will continue to be unknown.

Experience from the shipping industry and other business sectors such as financial institutions, public administrations and air transport have shown that successful cyber attacks can result in a significant loss of services.

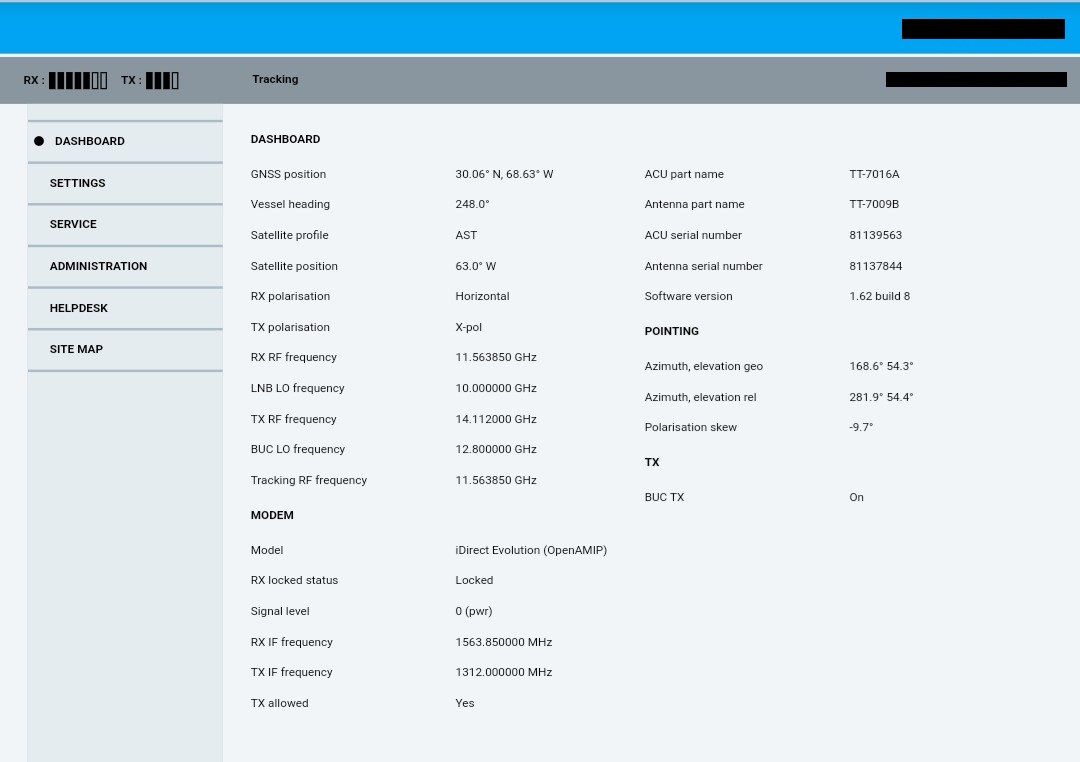

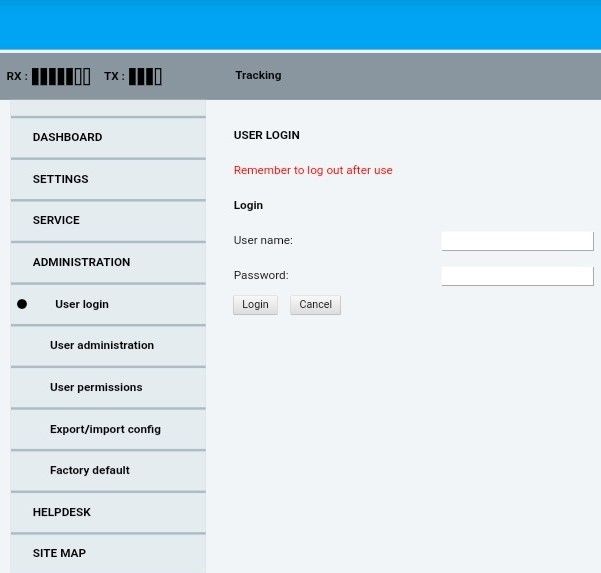

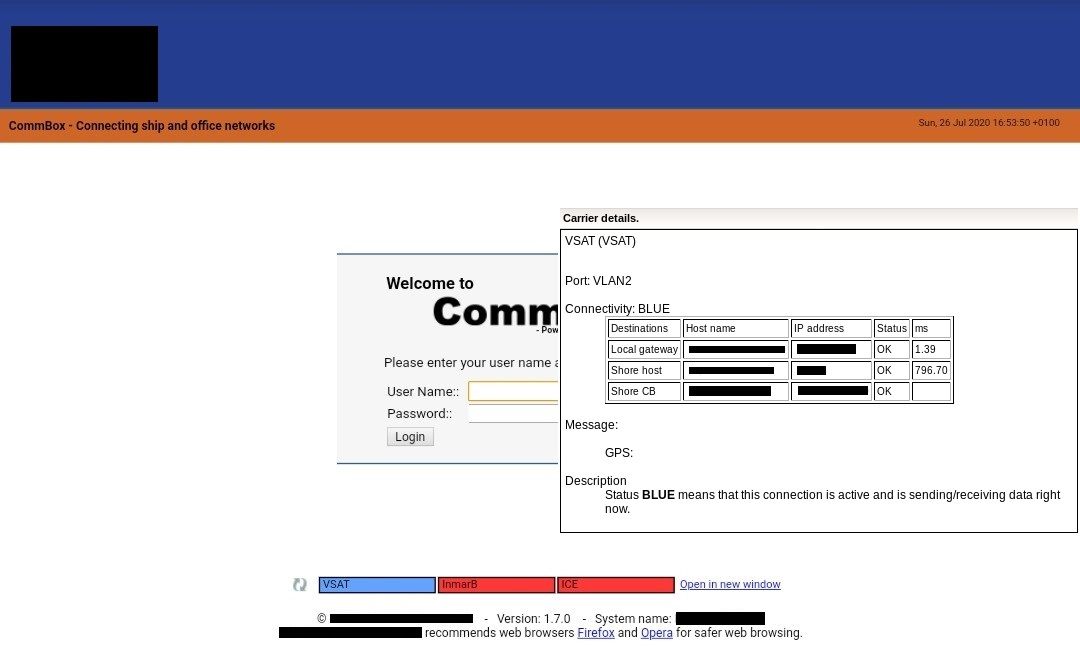

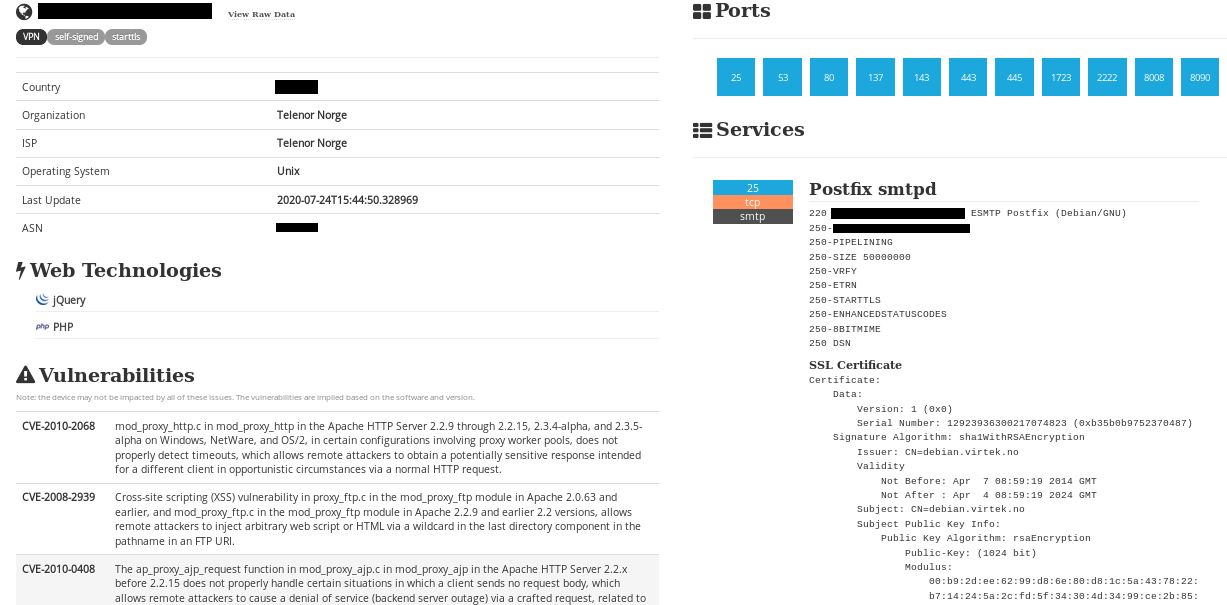

Modern technologies may add vulnerabilities to ships especially if there are placed on unsecured networks and given free access to the internet onboard. Additionally, shoreside and onboard personnel may be unaware that some equipment manufacturers maintain remote access to shipboard equipment and its network system. Unknown, and uncoordinated remote access to an operating ship should be an important part of the risk assessment.

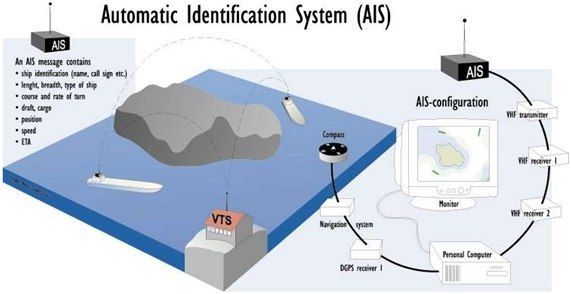

Gard recommends that companies fully understand the ship’s IT and OT systems and how these systems connect and integrate with the shore side, including public authorities, marine terminals and stevedores. This requires an understanding of all computer-based systems onboard and how safety, operations, and business can be compromised by a cyber incident.

Some IT and OT systems can be accessed remotely and may have a continuous internet connection for remote monitoring, data collection, maintenance, safety and security. These can be “third-party systems”, whereby the contractor monitors and maintains the systems from a remote location and can be both two-way data flow or upload-only.

Systems and workstations with remote control, access or configuration functions could, for example, be:

- bridge and engine room computers and workstations on the ship’s administrative network,

- cargo such as containers with reefer temperature control systems or specialised cargo that is tracked remotely,

- stability decision support systems,

- hull stress monitoring systems,

- navigational systems including Electronic Navigation Chart (ENC) Voyage Data Recorder (VDR),

- dynamic positioning systems (DP),

- cargo handling and stowage, engine, and cargo management and load planning systems,

- safety and security networks, such as CCTV (closed circuit television),

- specialised systems such as drilling operations, blow out preventers, subsea installation systems,

- Emergency Shut Down (ESD) for gas tankers, submarine cable installation and repair.

Below are some common cyber vulnerabilities, which may be found onboard existing ships, and on some newbuild ships:

- obsolete and unsupported operating systems,

- outdated or missing antivirus software and protection from malware,

- inadequate security configurations and best practices, including ineffective network management and the use of default administrator accounts and passwords,

- shipboard computer networks lacking boundary protection measures and segmentation of networks,

- safety critical equipment or systems always connected to the shore side,

- inadequate access controls for third parties including contractors and service providers.

Recommendation No.3: Provide proper onboard awareness and training

Today, the weakest link when it comes to cyber security is still the human factor. It is therefore important that seafarers are given proper training to help them identify and report cyber incidents.

The latest cyber security surveys show that the industry is more aware of the issue and has increased cyber risk management training, but there is still room for improvement. This has also been confirmed by the 2018 Crew Connectivity Survey by Futurenautics Maritime group with partners, where only 15% of seafarers acknowledge having received cyber security training, and only 33% said the company they last worked for had a policy of regularly changing passwords on board.

When assessing cyber risks, both external and internal cyber threats should be considered. Onboard personnel have a key role in protecting IT and OT systems but can also be careless, for example by using removable media to transfer data between systems without taking precautions against the transfer of malware. Training and awareness should be tailored to the appropriate seniority of onboard personnel including the master, officers and crew.

Gard have previously, together with DNV-GL, published a free to download and share cyber security awareness campaign to build competence towards crew and others – focusing on daily tasks and routines, with the aim to de-mystify the cyber issues for “normal people”. The material is not intended to suggest any industry changes or rule changes, but rather changes in the way people behave and act.

Lastly, we recommend everyone to stay cyber alert and avoid all “COVID-19 phishing” expeditions by:

- Exercise caution in handling any email with a COVID-19 related subject line, attachment, or hyperlink, and be wary of social media pleas, texts, or calls related to COVID-19.

- Use trusted sources—such as legitimate, government websites for up-to-date, fact-based information about cyber security and COVID-19.

- Do not reveal personal or financial information in email, and do not respond to email solicitations for this information.

- Remember to disconnect or close temporary remote access given to any external party after finishing the job.

Source: gard.no