e-Navigation is perhaps the most controversial topic in the future technological direction of the shipping industry. It is being actively pursued by regulators and regional authorities with the EU taking a leading role.

Proponents and regulators alike see e-navigation as a universal force for good that will among other things; improve safety, protect environments and enhance the commercial operation of ships and ports.

Others view it with suspicion believing that there are ulterior motives behind its development and that there is little support for some of the declared aims of the various projects espousing it.

Before exploring the concept further, it is necessary to look at the developments that have taken place in navigating technology and regulatory moves over the last two decades.

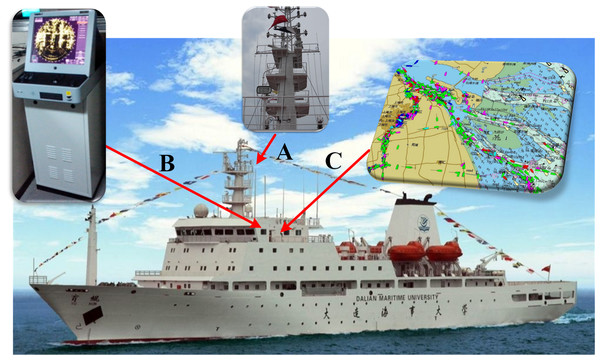

Essential e-navigation equipment

Modern ships are obliged to carry an extensive array of navigation and control systems and equipment on the bridge most of which have evolved at different periods in time over the past 60-70 years. The most recent system to have been mandated under SOLAS is ECDIS but it will still be some time before all affected vessels are required to be equipped and there will also be a significant number of ‘smaller’ ships below 3,000gt that are not required to install an ECDIS.

As a consequence of the continual addition of new equipment, many ships have a bridge comprised of disparate stand-alone systems. On newer vessels it is possible to integrate systems so that two or more can share data or sensor input with most of the very latest vessels having integrated navigation systems (INS) or integrated bridge systems (IBS).

There is a deal of confusion over the difference between the two terms and many consider them interchangeable. The IMO however does have different definitions, an IBS is defined in Resolution MSC.64(67) and an INS in MSC.86(70).

Comparing the definitions shows that an INS is a combination of navigational data and systems interconnected to enhance safe and efficient movement of the ship, whereas IBS inter-connects various other systems to increase the efficiency in overall management of the ship. More specifically, the IMO definition of an IBS applies to a system performing two or more operations from:

- passage execution;

- communication;

- machinery control;

- Loading, discharging and cargo control and safety and security.

By contrast the IMO defines three versions of an INS with each ascending category also having to meet the requirements of lower categories:

- INS(A), that as a minimum provide the information of position, speed, heading and time, each clearly marked with an indication of integrity.

- INS(B), that automatically, continually and graphically indicates the ship’s position, speed and heading and, where available, depth in relation to the planned route as well as to known and detected hazards.

- INS(C), that provides means to automatically control heading, track or speed and monitor the performance and status of these controls.

The two definitions do not have a common requirement as to the navigation element so it cannot be said that an IBS is an extended INS although many consider this to be the case.

The difference between the two is likely to disappear gradually as most shipowners are specifying high degrees of integration for new vessels in many cases going beyond that defined as an IBS. Both systems along with ECDIS are seen as being essential for the concept of e-navigation to be given a framework and direction.

Integrated systems and VDR have a common element in that both bring together data from disparate systems. In fact VDRs, as opposed to simplified versions (S-VDRs), were made more possible by integrated systems than perhaps any other development in navigation technology or regulation.

There is no doubt that there are significant advantages for navigators from integrated systems since it is possible to monitor and use all systems and instruments from a single work station. In addition, an integrated system with several work stations and screen confers a high degree of redundancy and system availability. The inclusion of ECDIS also permits passage planning and chart work to be done on the main bridge as opposed to in the chart room.

Every major navigation system provider offers an integrated system of some description as well as offering stand-alone systems. The systems are sold under brand names and include SAM Electronic’s NACOS, Kelvin Hughes’ Manta Bridge, Sperry Marine’s Vision Master, Raytheon Anschütz’ Synapsis and Kongsberg’s K-Master among many.

Defining e-navigation

Exactly what constitutes e-navigation is difficult to pin down. As far as the IMO is concerned it has its roots in the MSC(81) meeting in 2006 when a roadmap aiming for eventual implementation in 2013 was drawn up. By 2009 it had defined e-navigation as;

- E-navigation is the harmonised collection, integration, exchange, presentation and analysis of marine information on board and ashore by electronic means to enhance berth to berth navigation and related services for safety and security at sea and protection of the marine environment.

- E-navigation is intended to meet present and future user needs through harmonisation of marine navigation systems and supporting shore services.

Today the IMO is still discussing e-navigation with the latest developments described later in this chapter. However, the idea has much earlier roots and could be traced back to the EU ATOMOS project begun in 1992. ATOMOS was an acronym for Advanced Technology for Optimizing Manpower on Ships, and its goal was simply to find ways to reduce manning on EU ships as a means of making them more competitive.

At the time the EU felt that European shipping was losing out to Asian and Eastern European competitors who had lower wage costs and could therefore consistently undercut European operators. In the early 1990s it was wages and not fuel that constituted the greatest part of an owner’s outlay.

The summary document of the first ATOMOS project (there were to be at least three more stages) contained the following conclusion:

In terms of significance, many of the ATOMOS results should prove to be of substantial value. It is no secret that competition in the shipping industry is increasing day by day, with European shipowners being under constant pressure from third-world owners, or owners operating under third-world flags. The developments in the Soviet Union has not eased the situation for the EU fleet.

Much related to the issue of competition is the issue of maritime safety, however very often in reverse proportion. ATOMOS research has found that everything else equal, a low-manning ship equipped with ATOMOS technology is more competitive than a similar vessel equipped with conventional technology.

A further finding of research is that modern, low manned, high-tech ships are (at least) as safe as conventional ships. Many of the technologies looked into during the ATOMOS project shows great potential for an even further increase in maritime safety, an increase that could easily become mandatory, and an increase that might not be possible for vessels with conventional equipment.

Given the trends outlined very briefly above, and given any EU owner operating conventionally equipped vessels profitably today, the combined ATOMOS results indicates that competitiveness, safety and profits would increase by the utilisation of high-tech vessels.`

While it may not be recorded in the ATOMOS documents, there was a belief that the project could eventually lead to unmanned ships being operated remotely by shipping companies and shore traffic controllers Perhaps realising that such a scenario was not going to be an easy sell, the project morphed in to something less revolutionary and aimed more at safer shipping.

The first summary document contains hints at what the IMO would be asked to promote and which will be recognised as the core elements of e-navigation.

For example:- ‘the aim was to develop and integrate voyage planning, track planning and navigation tools such as electronic seacharts and situation analysis in order to minimize manpower needs and operator workloads in the ship control center. The direct consequence of the research was expected to provide means for optimized voyage plans with respect to economy and safety, taking account of fuel consumption, weather, wave data and other information. Further, the track planning part of the system was expected to increase safety by providing decision support during close encounters with other vessels, based on the international rules for collision avoidance’.

And ‘work was undertaken with the objective of examining current approaches to the integration of navigation, cargo handling and the control and monitoring of machinery to allow them to be performed, under normal operational conditions, by one man at a centralized ship control station. By considering factors such as ergonomic layout, man/machine interfaces and the optimization of operating procedures, the aim of the task was to produce guidelines for the safe and efficient implementation of centralized ship control stations’.

It is interesting to note that the idea of unmanned ships has not gone away and between 2012 and 2015 the EU funded the Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks (MUNIN) project which according to the official description had the specific tasks to:

- Develop the technology concept needed to implement the autonomous and unmanned ship.

- Develop the critical integration mechanisms, including the ICT architecture and the cooperative procedural specifications, which ensure that the technology works seamlessly enabling safe and efficient implementation of autonomy.

- Verify and validate the concept through tests runs in a range of scenarios and critical situations

- Document and show how this technology, together with new and more centralized operational principles gives direct benefits for non-autonomous ships, e.g., in reduced off-hire due to fewer unexpected technical problems etc.

- Document how legislation and commercial contracts need to be changed to allow for autonomous and unmanned ships.

- Provide an in-depth economic, safety and legal assessment showing how the MUNIN results will impact European shipping competitiveness and safety. Further MUNIN’s results will provide efficiency, safety and sustainability advantages for existing vessels in short term, without necessitating the use of autonomous ships. This includes e.g. environmental optimization, new maintenance and operational concepts as well as improved bridge applications.

It is clear that the EU is determined to follow through on the original intentions of the ATOMOS projects but there does not appear to be much international interest in the idea outside of Europe.

Even so, the IMO has added the concept of unmanned vessels to its safety agenda and at MSC 98 in June 2917 it considered a proposal on how IMO instruments might be revised to address the complex issue to ensure safe, secure and environmentally sound operation of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS), including interactions with ports, pilotage, responses to incidents and marine pollution.

It was considered essential to maintain the reliability, robustness, resiliency and redundancy of underlying communications, software and engineering systems. As a starting point, MSC agreed to start a regulatory scoping exercise over the four sessions of the Committee, until 2020, which would take into account the different levels of automation, including semi-autonomous and unmanned ships.

In the summer of 2015 a new project was announced to be led by Rolls-Royce. The Advanced Autonomous Waterborne Applications Initiative will produce the specification and preliminary designs for the next generation of advanced ship solutions. The project is funded to the tune of some €6.6Mn by Tekes (Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation) and will bring together universities, ship designers, equipment manufacturers, and classification societies to explore the economic, social, legal, regulatory and technological factors which need to be addressed to make autonomous ships a reality. The project will run until the end of 2017 and it aims are to pave the way for solutions – designed to validate the project’s research.

A separate project involving Kongsberg is also to begin in 2017 off the Norwegian coast. Although an autonomous ship is already technically feasible, their use would not currently be permitted for anything but domestic operation and even then there would likely be problems with commercial support.

Implementing e-navigation

At NAV 59 in September 2013 the IMO re-established a Correspondence Group on e-navigation under the coordination of Norway. The group included many flag states and industry bodies along with organisations such as the IHO and IMSO. The terms of reference of the group for those interested in further research are set out in document NAV 59/20, paragraph 6.37.

The Correspondence Group completed a report in March2014 which was discussed at the inaugural meeting of the IMO’s Sub-Committee on Navigation, Communications and Search and Rescue (NCSR) in July 2014 and passed to the MSC meeting in November 2014.

The report contained an e-navigation Strategy Implementation Plan (SIP) which can be accessed at the Norwegian Coast Guard website. The SIP sets up a list of tasks and specific timelines for the implementation of ‘prioritised e-navigation solutions’ during the period 2015-2019. Several ‘solutions’ are included in the SIP of which five have been prioritised.

Using the numbering given in the plan, the five prioritised solutions are:-

- S1: improved, harmonized and user friendly bridge design;

- S2: means for standardized and automated reporting;

- S3: improved reliability, resilience and integrity of bridge • equipment and navigation information;

- S4: integration and presentation of available information in graphical displays received via communications equipment; and

- S9: improved communication of VTS Service Portfolio.`

Apparently S1, S3 and S4 address the equipment and its use on the ship, while S2 and S9 address improved communications between ships and ship to shore and shore to ship.

It is quite possible that the SIP will be revised over time but its existence now provides a structural framework in which further developments are likely to take place and also gives those involved in developing and using the technology needed to realise e-navigation further information to work with.

It could be argued that as long as all developments are related to the ship’s equipment, e-navigation is little more than the development of standards and integration of equipment that operates just as well on a standalone basis. This is a valid argument because even though ships above a certain gross tonnage will all be required to be fitted with an operational ECDIS meeting current requirements, there is in fact no obligation upon the ship’s officers to use it for navigation unless a flag state or the ship’s owners says otherwise.

However, point S9 of the SIP mentioned above would suggest that more control over vessel traffic management will be possible if ports and regional authorities wish to invest in appropriate equipment. Real time information on water depths, currents, wind and weather coupled with programmed vessel movements will potentially allow for more efficient traffic control and improved safety.

As things stand, ships – whether they are using ECDIS or not – must rely on data that is fixed either electronically in the ENC or in tide tables and printed publications. Despite ENCs being a recent development, in some cases the data used in their production may be many years old. The only dynamic data that is available is the wind speed and direction as recorded

on the ship’s instruments and water depth directly under the vessel. In situations where wind and tide are in conflict, expected water depths may not be made and the potential for grounding is very real.

In a port equipped with tidal gauges and buoys feeding real time data from sensors at appropriate locations, ships could be provided with far more accurate information that could be used to improve both efficiency and saving. Whether ports or other authorities will be prepared to invest in the equipment and systems needed to make e-navigation worthwhile will depend upon several factors. In many countries, the cost could be beyond the resources of the authorities and in some ports the level of traffic may not warrant any outlay.

At MSC95 in July 2015 it was decided that further work should be carried out on e-navigation with any likely developments coming in 2017 at the earliest. In particular the meeting approved the document Guideline on Software Quality Assurance and Human-Centred Design for e-navigation which has been issued as MSC.1/Circ.1512. Other work related to e-navigation put in train at MSC95 includes:

- Revised performance standards for Integrated Navigation Systems (INS) – it was agreed to review resolution MSC.252(83) relating to the harmonization of bridge design and display information. The MSC agreed to include this output in the 2016-2017 biennial agenda of the NCSR and in the provisional agenda for NCSR 3 with a target completion year of 2017;

- Guidelines and criteria for ship reporting systems – it was agreed to review resolution MSC.43(64), as amended, relating to standardization and harmonized electronic ship reporting and automated collection of on-board data for reporting. The MSC agreed to include this output in the 2016-2017 biennial agenda of the NCSR and provisional agenda for NCSR 3 with a target completion year 2017;

- General requirements for ship-borne radio equipment forming part of the GMDSS and for electronic navigational aids – it was agreed to revise Resolution A.694(17) relating to Built In Integrity Testing (BIIT) for navigation equipment. The MSC agreed to include this output in the post-biennial agenda (2018-2019) of the MSC with NCSR assigned as the coordinating body; and

- Guidelines for the harmonized display of navigation information received via communications equipment – it was agreed to include this output in the 2016-2017 biennial agenda for the NCSR and the provisional agenda for NCSR 3 with a target completion year of 2017.`

The second of the above items has been given high priority by several parties because it is aimed at relieving the burden on ships officers of completing customs, immigration and other forms and providing information on cargo manifests and hazardous cargo.

That must be a puzzling development to many port agents who routinely compile that information well in advance of a vessel’s arrival and merely require the addition of a signature and ships stamp on arrival. The signing and stamping of documents usually takes just a few moments during the agent’s visit which will still be necessary to deliver cash, spares, mail etc.

What does the IMO say about e-Navigation?

The IMO’s concept of e-navigation is not shared by all and interest in independent navigational Apps for mobile computing systems is growing among shipowners and other shipping bodies. Whether this is a trend that will continue is debatable. Some of the Apps do appear to have attracted devotees but unless there is a regulation that mandates the use of any Apps, the fact that they will not be universally adopted means that they could adversely affect safety under many circumstances.

It has been suggested that e-navigation would reduce the cost of maintaining existing aids to navigation. The argument for this is hard to justify because it would seem to imply that buoys and lights could be abandoned. Although that would be possible with the aids to navigation becoming merely items of data in an ENC, the consequences of a failure of satellite positioning systems or the onboard ECDIS would effectively leave the crew of a ship underway in restricted waters blind to all hazards and with no way of avoiding them short of their own experience and knowledge.

Just as with the use of existing navigational aids in the days before they were mandated, few can doubt that Apps will inevitably find their way on the bridges of some vessels. Their use restricted to the navigators’ own ships will not necessarily be contentious unless an incident results but where Apps are designed to interact with other ships the question of safety is paramount.

There are a very small number of Apps either in use of under development designed to be interactive with other ships. Some have even suggested that such apps could make ColRegs redundant as ships’ systems will be able to calculate and carry out appropriate manoeuvres. Such a use would almost certainly be resisted by navigators and regulators

alike because the manoeuvres chosen would not be predictable or even understandable to other vessels nearby that were not under the control of a similar App.

Whatever direction e-navigation does take, one thing that is certain is that national governments and bodies such as the IMO can only regulate for systems that are available and few national governments are in the position to invest much in the way of financial resources.

Source: shipinsight